Contamination, parched rivers and recurring floods expose the fragility of Europe’s water systems. Robust legislation exists, but governments are slow to act. Delivering water resilience requires leadership, investment and real accountability.

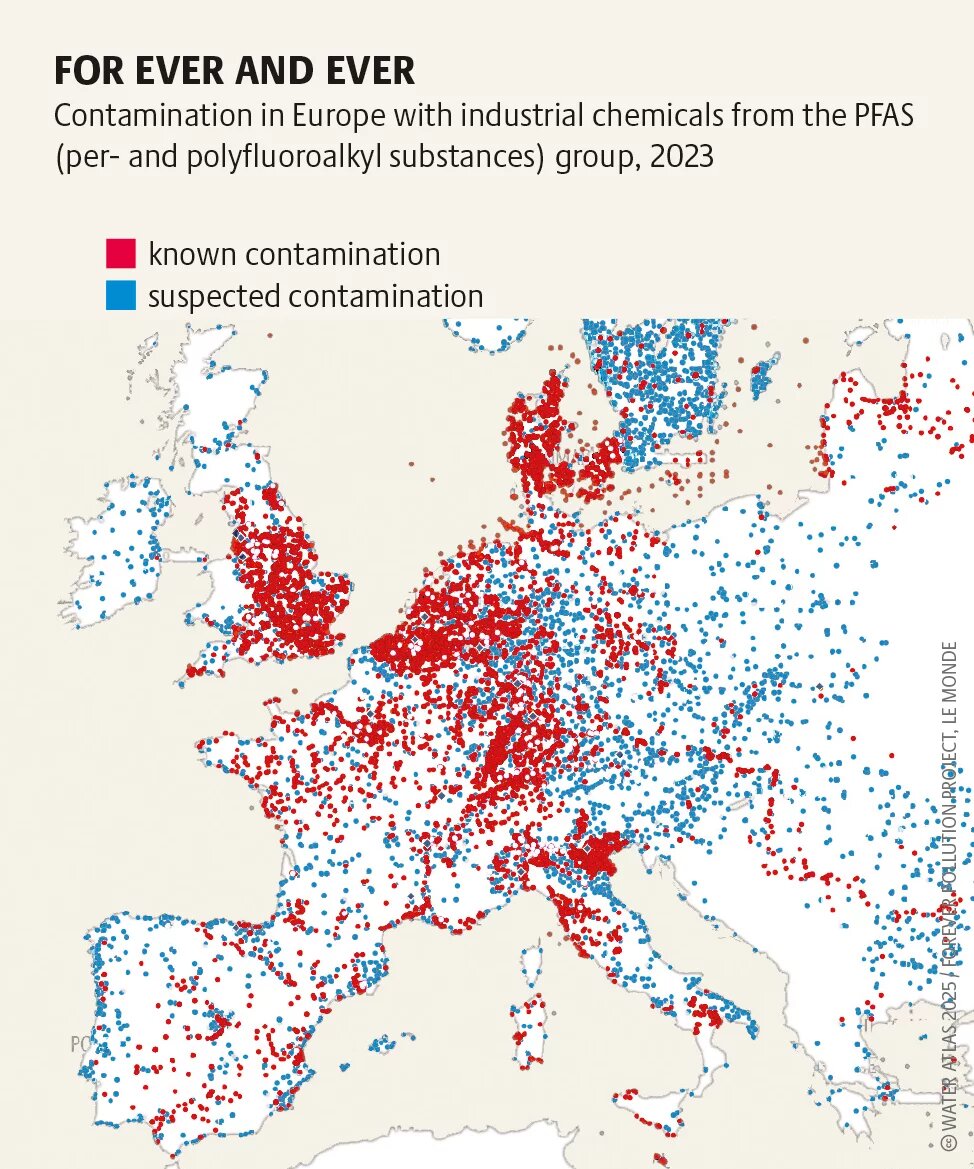

Europe's citizens, environment and economy rely fundamentally on water. Yet the rivers, lakes and groundwater aquifers in the European Union (EU) face intense and increasing pressures stemming from pollution and water mismanagement. Take PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), also known as forever chemicals, are widely found in European waters at levels far above safe thresholds in many areas. Other pressures include the alteration of river courses, disruption of natural flow patterns, and excessive water extraction. Europe is warming faster than any other continent, and the impacts on water are felt most acutely: more frequent floods and longer droughts. But the deeper crisis is one of inaction: the EU’s water laws exist, but are not properly enforced.

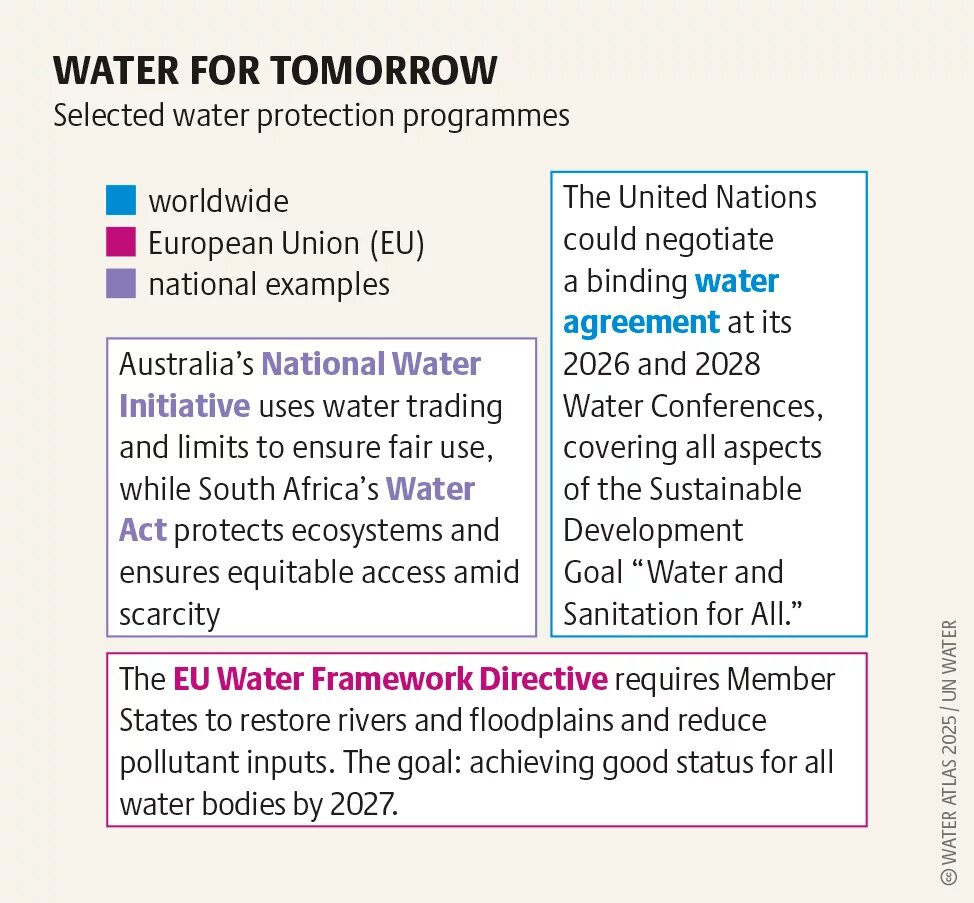

Adopted in 2000, the Water Framework Directive (WFD) is one of Europe’s most ambitious environmental laws. It introduced a legally binding, ecological and basin-based approach to water management. By mandating all Member States to achieve a good chemical and ecological status for their waters by 2027 at the latest, and by embedding principles of non-deterioration, transparency and cross-sectoral coherence, the WFD marked a decisive shift from reactive responses to specific water problems such as nitrate pollution.

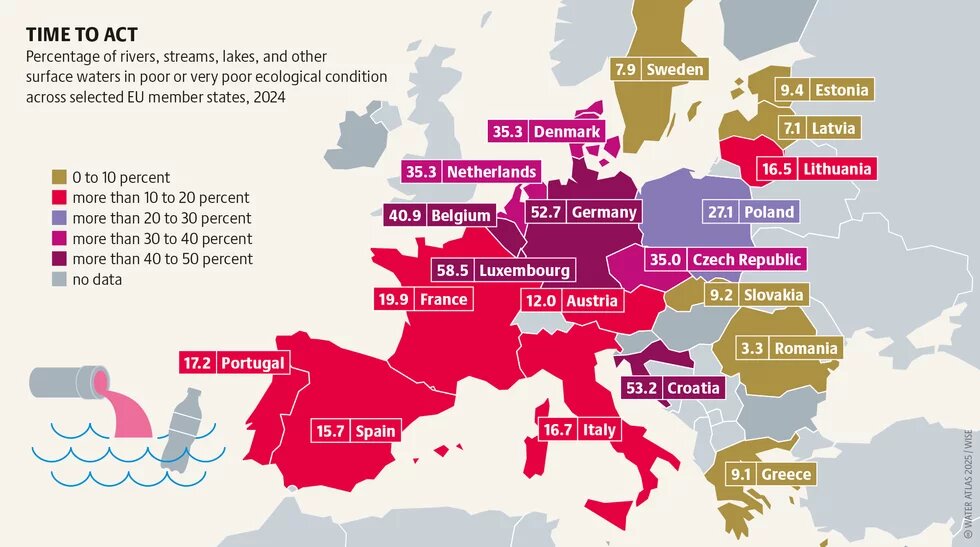

Yet 25 years after its adoption, the gap between ambition and reality is glaring. The European Commission’s 2024 implementation report confirms that the rate of water bodies reaching good status has stagnated, key measures are underfunded, and exemptions are overused. Enforcement remains the exception rather than the rule. The few infringement cases that the European Commission has opened so far regarding breaches of the EU’s flagship water law have not led to strengthened implementation. As a result, fewer than 40 percent of surface waters are in good status.

The Commission’s proposal to tighten regulatory standards for pollutants of emerging concern – such as PFAS – is still under negotiation. But Member States already have the legal tools to act: They can review industrial discharge permits, enforce stricter pesticide regulations, and impose national bans or restrictions on priority substances – all grounded in existing law, and all possible today.

This implementation phase is also the credibility test for the EU’s Water Resilience Strategy, put forward in June 2025 to tackle rising water scarcity, flooding, pollution, and ecosystem degradation across the continent. The WFD is what turns the Water Resilience Strategy’s targets into enforceable actions.

The cost of implementing the WFD is estimated at 89 billion euros for the period 2022–2027, a fraction of the cost of inaction: 238 billion euros for PFAS clean-up, 9 billion euros per year in drought-related losses, 7.8 billion euros annually in flood damage, and more than 50 billion euros each year in foregone benefits, including those arising from the failure to restore surface water.

As concluded by the fitness check evaluation of the EU water policy, the WFD does not need to be rewritten – it needs to be implemented and enforced. That is the foundation for water resilience, and for protecting citizens against floods and droughts, to safeguard drinking water, and ensure food security. The tools are already in place. What is needed now is political will, legal rigour, and sustained investment. This could turn 2027 into a launchpad for a new implementation phase, one focused on delivery, accountability and ecological recovery.

Another opportunity to repair the damage from the past is offered by the recently adopted Nature Restoration Regulation (NRR). This landmark piece of legislation aims to halt and reverse biodiversity loss across the EU and sets legally binding targets for restoring ecosystems – especially wetlands, peatlands, rivers, forests, grasslands, and marine environments. Member States must draw up national plans to restore at least 20 percent of the EU’s land and sea areas by 2030, and all degraded ecosystems by 2050. A key element of the law is the restoration of natural processes, such as rewetting peatlands or reconnecting rivers with floodplains, which also contribute to climate mitigation and adaptation. The law reflects a growing recognition: healthy ecosystems underpin food security, water quality, flood protection, and climate resilience. As part of the European Green Deal and EU’s Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, the Nature Restoration Law marks a major shift from conserving what remains to actively restoring nature at scale. It must be implemented in concert with the WFD and other nature laws.

New geopolitical and economic pressures are looming – from the EU’s industrial competitiveness agenda to the demands of the energy transition – and they may test the strength of Europe’s environmental laws. As Member States ramp up investments in hydropower, mining of critical raw materials, and infrastructure, there is a real risk that WFD safeguards may be weakened in the name of flexibility or expediency. Protecting the Directive from such pressures is crucial. Water resilience must remain central to the EU’s broader policy direction. This will also influence the EU’s standing globally, since both the WFD and NRR serve as models for water governance and nature restoration worldwide.